🫧 Investing in a Bubble

How to stay invested without losing your head

Welcome to the Free edition of How They Make Money.

Over 270,000 subscribers turn to us for business and investment insights.

In case you missed it:

🫧 Is it a Bubble?

It’s the single most persistent question in the market today. CapEx is ramping, valuations are soaring, and the hype is deafening. Yet the earnings are real, margins are expanding, and demand is unprecedented.

That’s the tension Howard Marks addresses in his latest memo.

Marks is the co-founder of Oaktree Capital and one of the most respected investors of our time. His memos are thoughtful, long-cycle reflections on risk, psychology, and capital allocation.

Warren Buffett once put it plainly:

“When I see memos from Howard Marks in my mail, they’re the first thing I open and read. I always learn something.”

In his new memo, Marks cuts through the noise surrounding the AI boom. Rather than trying to forecast prices or call a market top, he examines behavior.

There are really two conversations happening at once:

• The scale and pace of the AI infrastructure buildout.

• How that buildout is being priced in public and private markets.

Marks’ conclusion is deliberately measured, but unmistakably cautious. If AI enthusiasm doesn’t produce a bubble, he writes, it will be a first.

In this article, we’ll pull out the memo’s most important insights and pair them with visuals to help frame where we are in the cycle.

Not to call a top. Not to predict what happens next. But to understand how bubbles work and what to do about them.

Today at a glance:

How Bubbles Form

Two Types of Bubbles

The Uncertainty Stack

The Debt Problem

How Investors Should Think

1) How Bubbles Form

Bubbles don’t begin with bad ideas.

They begin with good ideas taken too far.

A new technology appears and feels genuinely different. It promises to change how the world works. Early adopters are rewarded, often dramatically. Those early successes validate the story, and that’s when excitement turns into FOMO (fear of missing out). This is true for both the industry (AI chips) and the market (AI stocks).

People stop asking “Is this real?” and start asking “How do I get exposure?”

Skepticism feels costly. Caution feels like falling behind.

CEOs, from Mark Zuckerberg and Sundar Pichai, have made clear that underinvesting in AI is a far greater risk than overinvesting. The danger arises when individual investors adopt a similar mindset, even when they face no existential threat.

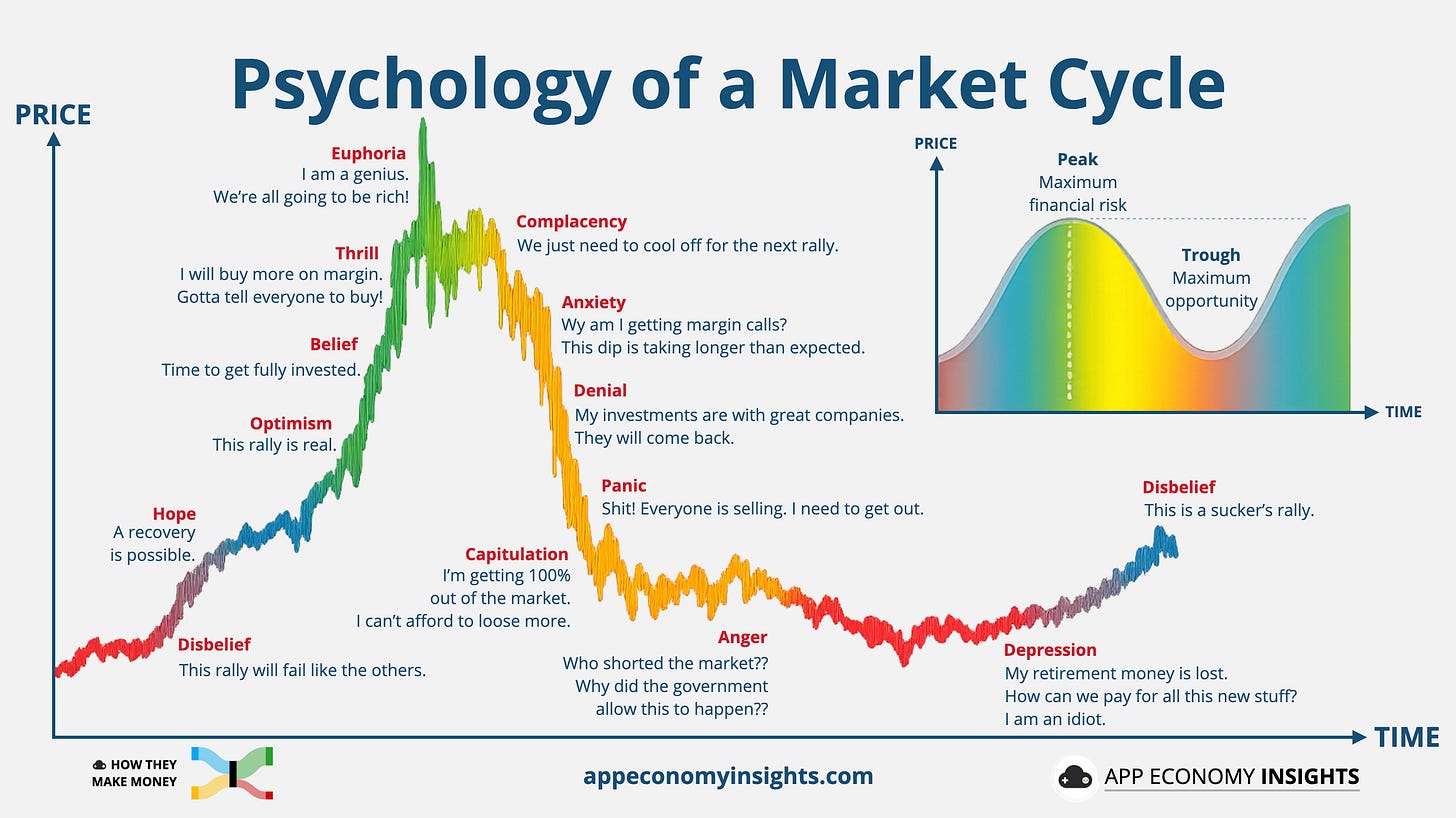

I recreated this classic market psychology chart (the original from Wall Street Cheat Sheet is hard to read, and the website is no longer maintained). It captures the raw emotions that repeat across every market cycle. I’ll leave it to you to decide where we are today.

At the core, bubbles aren’t caused by technology itself.

They’re caused by excessive optimism applied to something new.

Newness matters because it removes constraints. With no history to anchor expectations, the future feels limitless. In turn, valuations stretch beyond what can be justified by predictable earnings power, not because investors are foolish, but because imagination fills the gaps where data doesn’t yet exist.

That’s why bubbles follow such a consistent pattern.

Human psychology doesn’t change.

An early success breeds confidence.

Confidence turns into extrapolation.

Extrapolation invites speculation.

Speculation lowers standards.

Eventually, prices stop reflecting likely outcomes and start reflecting potential.

One of Howard Marks’ most important observations is that debating whether something is a bubble can distract from better judgment. You don’t need a label to behave intelligently. You just need to recognize when the pendulum has swung too far.

That’s usually when we see:

IPOs and private funding rounds surge, often at extreme valuations.

Narratives overpower fundamentals, with stories running ahead of cash flows.

Returns concentrate in a few stocks, pulling in passive and momentum capital.

FOMO-driven speculation replaces risk assessment.

Financial engineering fills the gaps through leverage or circular deals.

All of those ingredients are undeniably present in today’s market.

As Sir John Templeton famously warned, the four most dangerous words in investing are: “This time it’s different.”

AI may indeed be transformative, and the massive CapEx ramp justified.

But when success is priced as inevitable, future returns tend to disappoint.

2) Two Types of Bubbles

Not all bubbles are the same.

One of the most useful distinctions in Marks’ memo comes from a simple idea: some bubbles form around real technological inflections, while others are built almost entirely on financial excess.

Understanding which one you’re dealing with matters far more than debating whether something is “a bubble” at all.

🏠 Mean-reversion bubbles

These are the destructive kind.

They’re fueled by financial engineering, leverage, or the promise of returns without risk. Nothing fundamental has changed in the real economy. When enthusiasm fades, prices revert, and little of lasting value remains.

Think subprime mortgages, portfolio insurance, or other fads that rise and fall without moving the world forward. These bubbles destroy wealth, full stop.

🤖 Inflection bubbles

They form around technologies that genuinely change society: railroads, electricity, aviation, the internet, and now AI.

In these cases, the direction is right. The timing and pricing are often wrong.

In inflection bubbles, capital arrives faster than the technology can mature. Infrastructure is overbuilt, competition intensifies, and returns collapse, even as real-world adoption accelerates.

The world moves forward. But not all investors remain unscathed.

Marks makes a crucial point here: inflection bubbles can accelerate progress precisely because they waste capital. The speculative mania compresses decades of experimentation, trial-and-error, and infrastructure buildout into a short period. Much of the money is lost, but the foundation for future productivity is laid.

That creates a paradox investors often miss.

A technology can be world-changing and a terrible investment at certain prices.

Progress for society does not guarantee profits for shareholders.

AI clearly fits the inflection-bubble category. Its potential is real, and its impact is hard to dispute. But that doesn’t make every investment tied to AI sensible, or every valuation defensible.

Which leads to the most uncomfortable part of inflection bubbles: the end state is unknowable.

3) The Uncertainty Stack

The defining feature of inflection bubbles is their unknowability.

Analysts already struggle with forecasting growth rates or margins for the next quarter. They’re being asked to price an end state that doesn’t yet exist, and may look nothing like today’s assumptions.

Google’s stock swung from uninvestable to inevitable in just a few years. Not because the future became predictable, but because new facts kept changing the narrative.

Howard Marks returns to this point repeatedly in his memo: the biggest risk isn’t being wrong about AI’s importance, but overestimating how much can be known in advance.

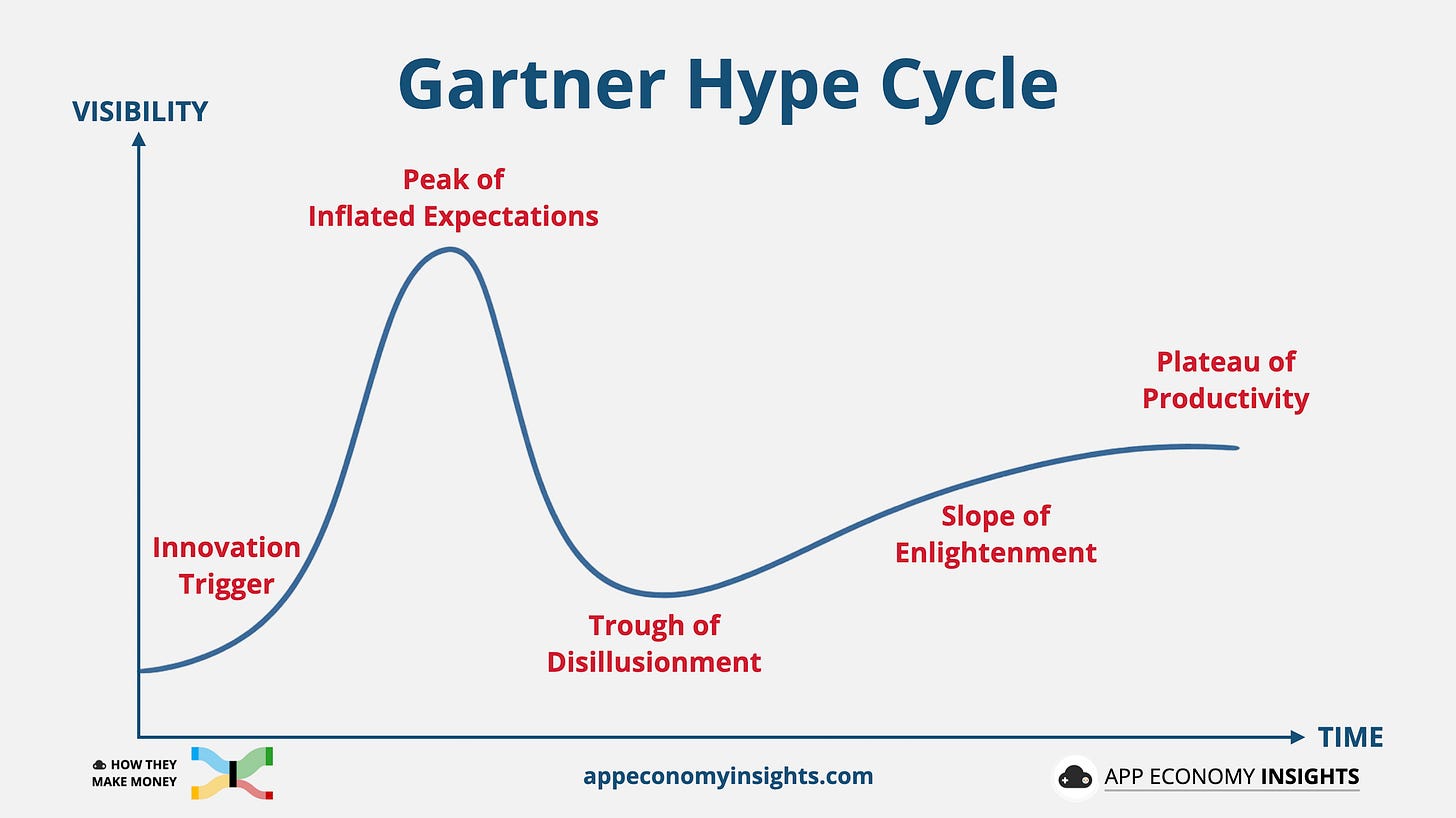

Technologies don’t move through the cycle uniformly. The Gartner Hype Cycle reminds us that expectations, adoption, and economic maturity rarely advance in lockstep. In AI, different layers are likely sitting in very different places, which makes pricing the “end state” especially fragile.

Start with the most basic question.

Who actually wins? History is brutal here. Revolutionary technologies don’t reward early leaders by default. Railroads, autos, search, and social media all reshuffled incumbents. Some of today’s frontrunners may dominate. Others may be displaced by companies that do not yet exist.

Who captures the profits? Even if AI adoption explodes, that doesn’t mean vendors earn excess returns. Productivity gains can accrue to customers instead. Cost savings may be competed away through lower prices. A technology can transform industries without enriching the companies that provide it.

What does the market structure look like? Monopoly, duopoly, competitive free-for-all, or a layered ecosystem with a few winners and many marginal players? Each outcome supports radically different valuations, yet markets often price one as if it’s inevitable.

How durable are today’s assets? Chips, data centers, and models are expensive, with a useful life still TBD. Rapid innovation increases the risk that today’s infrastructure becomes obsolete before it recoups its cost. That matters enormously when assigning multiples or underwriting long-term cash flows.

How much of the growth is real demand? Marks highlights the risk of circular behavior: vendors selling to customers who are simultaneously funding them, or partners transacting to show progress. Activity can look explosive without being durable. To be sure, Goldman Sachs estimates that less than 15% of NVIDIA’s revenue will come from circular deals in 2027, so it’s not the main story as some analysts make it out to be.

Layer these uncertainties together, and a pattern emerges.

The future may be enormous, but its shape, timing, and economics are deeply unclear.

4) The Debt Problem

Most bubbles deflate. Debt is what makes them dangerous.

When outcomes are uncertain, equity absorbs mistakes, delays, and pivots. Debt does not. It assumes cash flows will arrive on time and at scale to service fixed obligations. That’s a reasonable assumption in stable industries. It’s a fragile one in fast-moving technological revolutions.

This is where Howard Marks draws his sharpest line. Financing uncertainty with equity is normal. Financing conjecture with debt is not.

AI infrastructure sits uncomfortably close to that boundary. Chips, data centers, and models are expensive, capital-intensive assets with useful lives that are hard to forecast. Their economics depend on demand that may accelerate, stall, or shift as the technology evolves.

Dark fiber vs. dark GPUs

The dot-com era left behind dark fiber, massive infrastructure built for internet traffic that didn’t yet exist. It was a gamble on future demand that arrived too late.

In a recent a16z interview, Gavin Baker put it simply:

“Contrast that with today, there are no dark GPUs.”

AI looks different. We aren’t building ahead of demand. We are chasing it. GPU capacity is heavily utilized, and supply is constrained. Unlike fiber in 2000, today’s compute isn’t sitting idle.

High utilization acts as a floor. It reduces the risk of near-term write-downs and confirms that today’s CapEx is responding to genuine, cash-paying demand. But high utilization only proves the utility is real. It doesn’t prove the profitability is permanent.

And that doesn’t eliminate the role debt can play in turning uncertainty into fragility.

Who funds the buildout matters

So far, much of the AI capex ramp has been funded internally. The largest platforms generate tens of billions of dollars in annual free cash flow from their existing businesses, allowing them to scale aggressively without immediately stressing their balance sheets.

Even OpenAI has largely relied on equity-based partnerships and long-term commercial agreements to finance its cash burn, avoiding near-term balance-sheet pressure.

At the same time, the bond market has quietly become part of the financing stack.

Meta issued one of the largest corporate bond deals in history, raising roughly $30 billion across long-dated maturities as AI capex accelerated.

Alphabet and Oracle have both issued 30-year bonds in recent years, explicitly extending financing horizons to match long-lived AI and cloud infrastructure.

Amazon, already one of the largest capital spenders in the world, continues to pair massive AWS CapEx with regular access to debt markets to preserve flexibility.

None of this is reckless in isolation. These are high-quality issuers with strong cash flows. Credit markets are open because default risk looks remote.

The dilution risk

Compared to past bubbles, the system is less immediately fragile.

But it doesn’t make the capital immune to misallocation.

When CapEx is funded by free cash flow, the risk shifts from insolvency to dilution. Shareholders may avoid catastrophic outcomes while still paying through lower free cash flow, reduced buybacks, or years of subpar returns if investments fail to earn their cost of capital.

This is not 2000, but the buildout still comes at a cost.

5) How Investors Should Think

We are facing a self-aware bubble today.

Investors openly debate whether the AI boom is a bubble. Valuation multiples are scrutinized. Comparisons to 1999 are everywhere. That awareness doesn’t eliminate excess.

Two things can be true

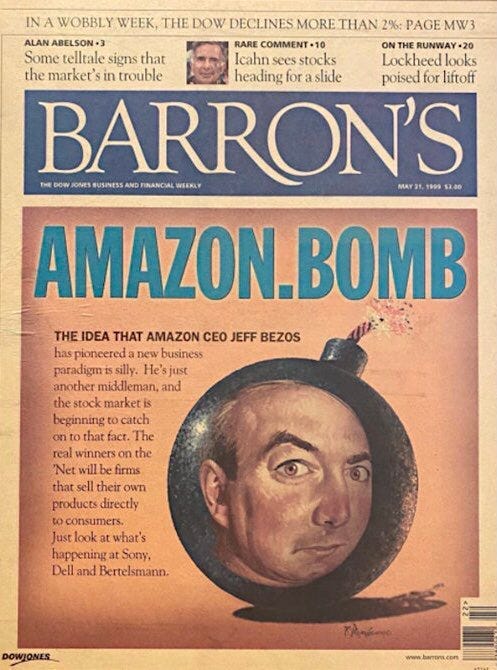

In May 1999, Barron’s ran its now-famous “Amazon.bomb” cover, warning that Amazon’s business model was unproven.

Amazon’s stock fell more than 90% over the next three years.

Twenty-five years later, the stock is up more than 50×.

The lesson: Being right about the destination (AI will change the world) doesn’t protect you from the journey (a potential massive drawdown).

The job isn’t to predict the outcome, but to survive the volatility along the way. That requires conviction without rigidity. Strong views, loosely held. And a willingness to change your mind as facts change.

The hardest part of investing through a potential bubble isn’t data or analysis. It’s behavior. In legendary investor Peter Lynch's terms, the most crucial organ in investing is not the brain. It’s the stomach.

No one knows whether today’s enthusiasm fades quietly or ends painfully. Howard Marks borrows from Mark Twain and argues that history doesn’t repeat, but it often rhymes. Painful endings are more common than gentle ones. The trillion-dollar question is when.

Fed Chair Alan Greenspan famously coined the term “irrational exuberance” in 1996. The SP& 500 more than doubled from here before peaking in March 2000. The lesson is uncomfortable but clear: trying to call market tops is a hazardous hobby. Peter Lynch noted that more money is lost attempting to time corrections than in the corrections themselves.

The art of sitting on your hands

Staying invested through uncertainty is a prerequisite for compounding returns. Yet it’s the rule most often abandoned.

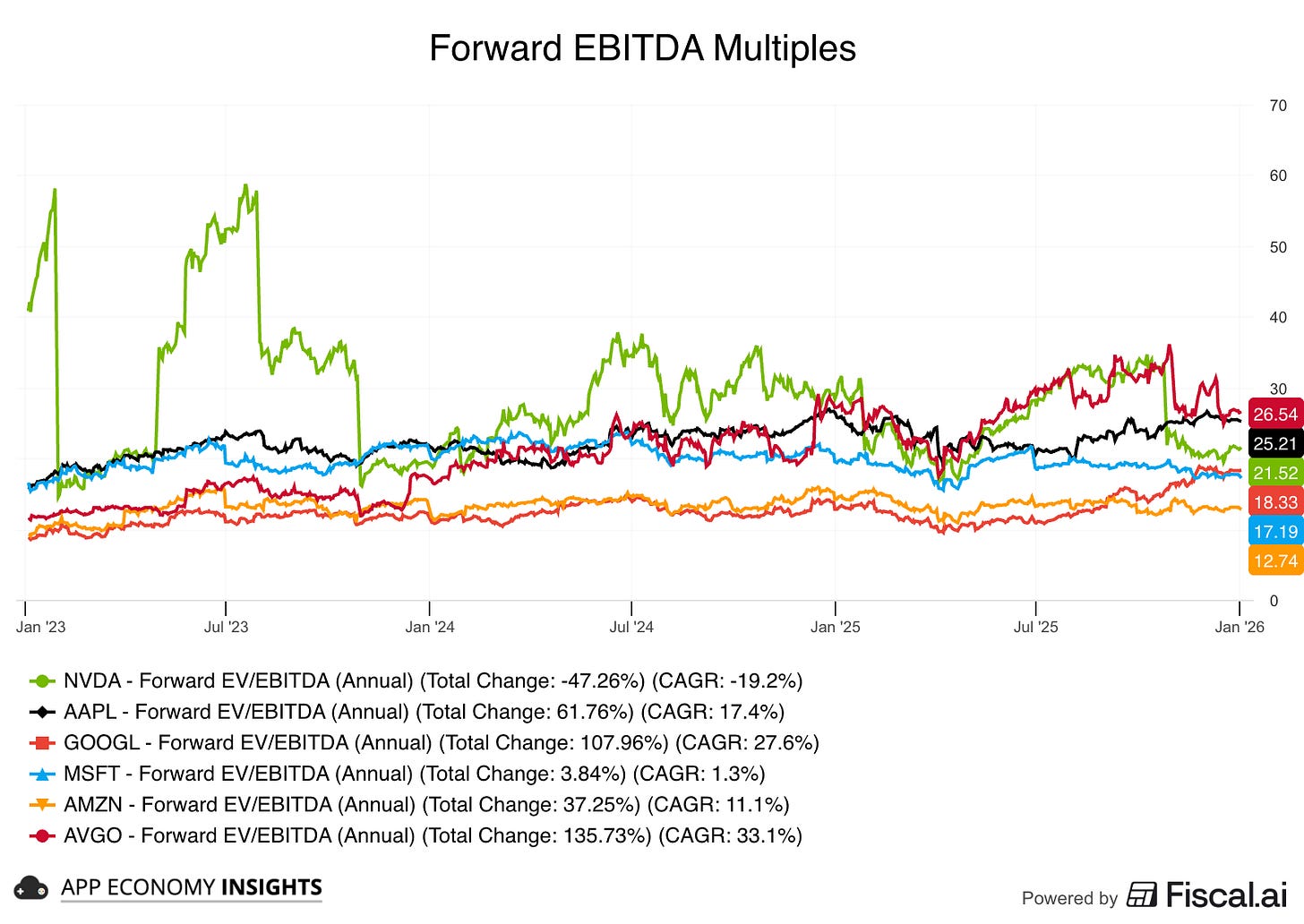

One practical way to apply a long-term mindset is to assess how much optimism is already embedded in prices, particularly among market leaders. As Marks puts it, valuations have been “high, but not crazy,” particularly relative to the underlying business momentum.

Marks’ advice is deliberately unspectacular: not all-in, not all-out. A moderate position, applied with selectivity and prudence.

Your edge

AI may prove to be the most important technology of our lifetime. It is also likely to produce excess, overbuilding, and painful corrections.

CEOs have no choice. They must over-invest to avoid extinction. Underinvesting is an existential risk they cannot take.

You do not face that constraint. You can sit on your hands. You can ignore the overpriced IPOs. You can diversify. That flexibility is not a weakness. It is your distinct advantage.

How to use it:

Separate belief from pricing: A company can change the world and still be a terrible investment at the wrong price.

Audit the balance sheet: In a storm, cash is oxygen. When capital becomes expensive, companies that need to borrow to survive often don’t.

Don’t mistake volatility for risk: Big drawdowns are the cost of admission in public markets. What Morgan Housel calls “a feature, not a bug.” You must have the stomach for 30%-50% drops to capture the long-term upside.

Avoid ruin: Stay away from leverage. Missing upside is uncomfortable, but being forced out is fatal. The goal is to stay invested long enough to benefit from what endures.

The investors who endure won’t be the loudest or the boldest. They will be the ones who stayed invested, selective, and humble. Long after the cycle has turned.

That's it for today.

Happy investing!

Want to sponsor this newsletter? Get in touch here.

Thanks to Fiscal.ai for being our official data partner. Create your own charts and pull key metrics from 50,000+ companies directly on Fiscal.ai. Save 15% with this link.

Disclosure: I own NVDA, AAPL, GOOG, AMZN, AVGO, and META in App Economy Portfolio. I share my ratings (BUY, SELL, or HOLD) with App Economy Portfolio members.

Author's Note (Bertrand here 👋🏼): The views and opinions expressed in this newsletter are solely my own and should not be considered financial advice or any other organization's views.

Top 👍

Hi,

Good to connect. I’m new to Substack after trading in my PPE and tools, and I now write about markets, risk, and the stories we tell ourselves to stay comfortable.

After the Close is less about prediction and more about process. Discipline over drama. Thinking clearly when the screens go dark. The writing is partly a way for me to slow things down and stay honest, especially in a space that rewards noise.

If you ever have a moment to look through it, I’d genuinely appreciate any feedback on the process. Good or bad is fine. I can handle it.

Cheers,

Andrew